The briefest of dry spells this morning was an unveiled signal to venture outward, so we loaded ourselves into our car and traversed the familiar road to Skei (pronounced like “shy”), a town we passed through days before on our trip with Arnor and Kari. Skei is home to a gift shop heavily favored by my parents–and apparently many other compatriots, as evidenced by the recognizably Midwestern gab overheard throughout the store. Our stop to refuel in the cafeteria upstairs was a fruitful one, as it provided my first opportunity to sample rømmegrøt, a traditional Norwegian delicacy that loosely translates to “cream porridge.” The dish is essentially a thickened paste made from flour, milk, and acidified cream (rømme is Norway’s equivalent of sour cream, though it is thicker than what you typically find in the U.S.), and is customarily topped with melted butter, sugar, and cinnamon. I give the experience a wholehearted thumbs up, and would happily eat it again.

Though my parents harbor a far more enthusiastic proclivity for gift shop browsing than I do, I was glad to have the occasion to cross a few final souvenir recipients off my list before our eventual journey home. I have been careful when spending my money in Norway to seek out items that have actually been produced here, and I was thrilled to finally locate a beautiful sweater from Dale of Norway, one of the country’s foremost textile companies, whose clothing–including all of the accompanying fabrics and accessories–is exclusively designed and created here. I plan to sport it proudly upon my return to the United States.

Alas, any farfetched fantasy of strolling around other parts of Skei was quickly dashed by the return of showers, so it was back to Sogndal–but not before a detour. The road back crosses through Fjærland, which, in addition to hosting the bokby from an earlier post, is also the home of the Norsk Bremuseum, or Norwegian Glacier Museum. Fjærland is a stone’s throw from the Jostedal Glacier, which looms as the largest glacier in continental Europe, so it is an apt home for such an attraction.

The bathroom mirrors in the museum are equipped with an unexpected defense mechanism.

I was pleased to find that the museum caters to even the most ignorant of travelers; at the risk of revealing my own miseducation, I started the visit learning the simple definition of a glacier. Commonly, at least per my own perception, we think of glaciers simply as large bodies of ice, but I’ve never truly known what distinguishes an actual glacier from any other formation of frozen water. As it turns out, glaciers are the product of many years of geological evolution, the result of accumulated snowfall that, through the interference of wind, cycles of freezing and refreezing, and other factors, becomes glacial ice, which is distinguished from ordinary ice by the fact that it is far denser and therefore more resistant to melting. Of course, as we know, even this higher resistance has been no match for human-made interference.

A fascinating subject highlighted by the museum’s exhibits is Norway’s harnessing of the glaciers as sources of energy. Tunnels underneath the glaciers funnel running water that melts from the ice into chambers that filter out sediment from the water into flushing channels, and then feed the remaining water into turbine stations that use the liquid as a source of kinetic energy. We often think about climate change as simply an existential threat to the icebergs and glaciers throughout the world, acknowledging that their melting will cause a cataclysmic rise in sea levels, but the museum exposed another angle to the problem. The loss of the glaciers would be catastrophic to countries like Norway that rely on them to be powerful fonts of clean energy.

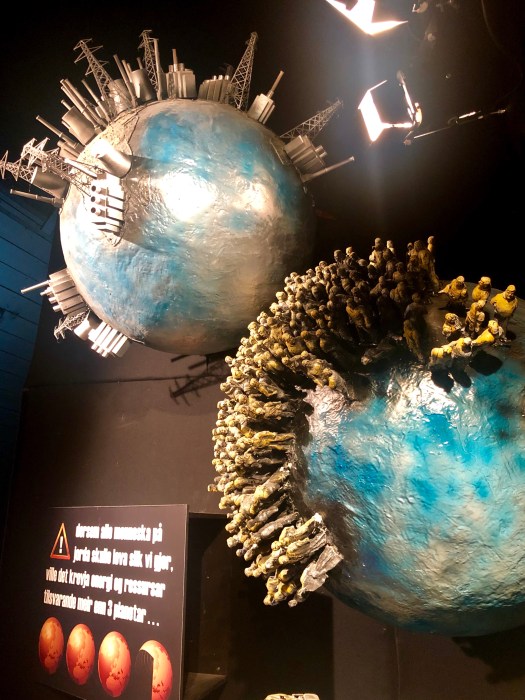

Appropriately–and refreshingly, from my American perspective–the museum takes an aggressive stance on portraying the urgency of the climate change crisis. A multimedia exhibit in one of the galleries takes guests through renderings of the various historical evolutions of our planet’s atmosphere, concluding with the current state of abuse at the hands of humankind. I was aghast at the end of the exhibit, where an interactive poll asked visitors whether they are optimistic about the current trajectory of our efforts to counteract the desecration we have wrought. A 3-to-1 majority in favor of optimism revealed the colossal challenge we still face to make clear the exigency of this problem and the rapidly closing time frame remaining to fix it.

To wrap our eventful day, we were overdue for a visit to Arnor and Kari, so we headed to their house in hopes of finding them. And just in time: we caught them as they were headed out the door for a shopping trip, but, in Arnor’s words, “it’s good to be a pensjonist“–retiree–because they could do that any other time. They demonstrated uncommon kindness, and turned around to invite us inside.

I am not fully convinced Kari is not a sorceress. Upon our arrival, she disappeared into the kitchen for what could not have been longer than 10 minutes, reemerging with a spread of food options that covered the entire table. I know I have written it before, but the thoughtful generosity we’ve been shown by relatives across the board cannot be overstated. The spread featured homemade sandwich buns, smoked salmon, boiled eggs, sandwich meats, pancakes (a smaller variety than we are used to in the U.S.; they are commonly enjoyed here as an accompaniment to afternoon conversations), tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, the aforementioned rømme, berry jam, butter, brunost (brown cheese, a Norwegian favorite), and one final item of particular local fame (or perhaps I should say infamy): the dreaded gamalost.

Gamalost translates literally to “old cheese,” and for good reason. One would be forgiven for not recognizing it as cheese at all; indeed, I mistook it for some kind of cake covered in brown sugar on first reckoning. It even resists attempts to slice it: the cheese crumbles more readily than it cuts, in truth. Although I have been cautioned many times on this trip by tales of gamalost‘s legendary repulsiveness, I consigned to trying it at least once if the opportunity presented itself (however, I would be lying if I claimed I was rooting for such a moment to actually materialize). And so I did. Mercifully, the specimen presented to us today seemed–with Arnor’s confirmation–to have been a more peaceful cousin of far more vile versions from years past, when the odor alone could clear a room. Nevertheless, while I can now claim to have tried Norway’s most horrifying culinary contribution, I won’t be rushing to my second instance any time soon (but I thank Kari and Arnor for the, er, unique experience).

Tomorrow will bring us the fortunate opportunity to join the beginnings of the apple harvest that takes place in the many orchards that span the various households in Sogndal. We will be eager participants, having spent many of our last several days confined to indoor activity. More on that soon!